Alvarado and Gilda Espinal, the coordinator of the Land Rights Project, spend almost half their time in the Property Institute offering assistance and oversight with the technical registration and titling processes. They have created manuals of correct processes and encouraged a more organized, transparent approach to titling land.

June 30, 2016

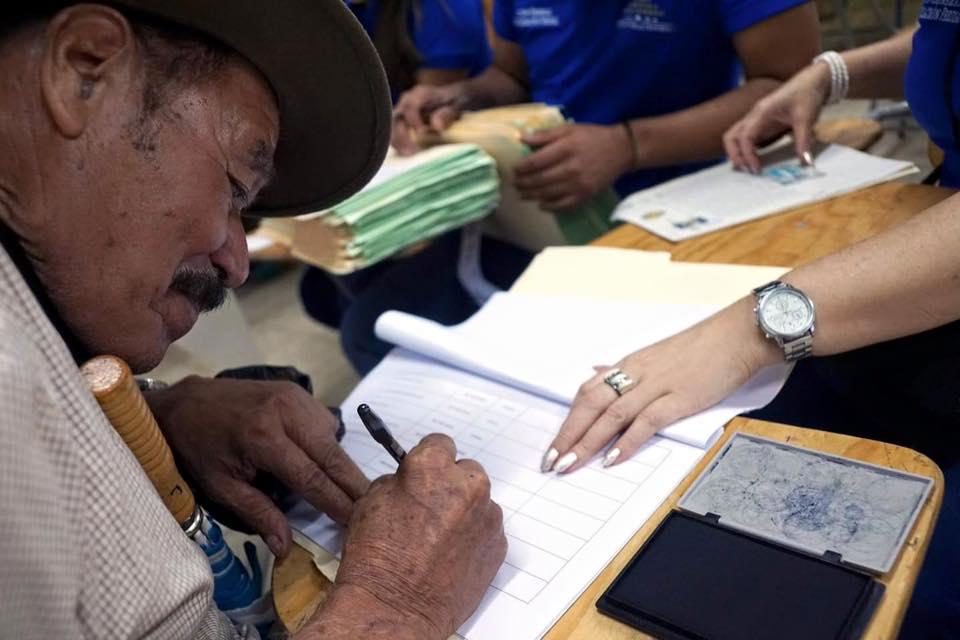

Last Monday, Honduras’ Property Institute delivered 639 property titles to residents of various neighborhoods in Tegucigalpa. For the recipients, many of whom had lived in their homes for decades, it was an emotional moment, the end of a process that had stretched on for years. These property titles proved at last that they were the rightful owners of their homes.

Despite an estimated one million unregistered plots of land in urban areas, over the past ten years, the Property Institute has only registered an average of 4,500 annually. The process of registering and titling land is long and complex, and sometimes it stalls completely. In 2015 and the beginning of 2016 the Property Institute delivered no titles at all.

The uncertainty of living in an unregistered home drastically affects the urban poor, who without a title, face the risk of losing their homes.

“Many of these people have lived on the property for a long time and are elderly now,” said Anajansi Alvarado, an auditor and investigator with ASJ’s (formerly known as AJS) Land Rights project. “If they die there is no guarantee that their family will inherit their property.”

Land is also many of these families most valuable asset, though without a legal title, this value is “trapped” – it can’t be mortgaged or used as collateral for a loan.

“Many of these people can’t find jobs, and the loans they are able to get with their titles allow them to start a business,” said Alvarado. “They could not have gotten this money otherwise. It gives them many more opportunities to improve their lives.”

The partnership with the Property Institute has not always been an easy one. In March of 2014, ASJ signed an agreement allowing ASJ to provide oversight and transparency to the Property Institute. But that year, titles were prepared sloppily, ignoring the manual and advice ASJ provided. The Land Rights project took a sample of titles to audit – every single one had an error.

ASJ said they couldn’t approve the delivery of the titles. Even seemingly small errors could cause big problems for the recipients. Names spelled incorrectly could invalidate the title, property titles with the name, for example, of the husband, but not the wife threatened equal ownership and inheritance. People with bad titles would have to return to the Property Institute and ask for a correction, an additional expense, and an undetermined wait.

Despite the protests of ASJ, the titles were delivered anyway.

The Land Rights project didn’t give up. They continued to meet with the Property Institute, offering advice and oversight and working slowly on improving policies, speeding up processes, and getting things right the first time.

Since 2014, ASJ has overseen the preparation of 9,220 property titles for plots of land in the two largest cities of Tegucigalpa and San Pedro Sula. What’s different about these 639 titles, however, is that they are the first that ASJ has observed from the beginning and the first that they certify as being fully correct, accurate, and legal.

The quality of these titles is directly tied to ASJ’s support, something the Property Institute acknowledged when they invited ASJ president Carlos Hernández to attend the event where he symbolically delivered titles to waiting families.

Juan Orlando Hernández, President of Honduras, also praised ASJ’s oversight, not just in the Property Institute, but in all the largest state entities.

These 639 titles are just the beginning of what the Land Rights project hopes will be a faster, more accurate, and more responsive process. Over a thousand more titles should be ready within the month, improving the prospects and security of many thousands of individuals.

The challenge of making systems work can be slow and difficult, but it can also be life-changing.

Doña Enemesia, aged 70, has lived for more than 30 years in her house in one neighborhood in Tegucigalpa. “Today I completed my dream to have my property title,” she told the Property Institute, who published her story on their Facebook page. “With my property title now I can fix my house. I can get a loan and my family can have a better life.”

“For us a title is just a piece of paper,” said Anajansi Alvarado, “but for the people receiving it, it means much more.”